For the past thirty five years, we’ve been working with mass timber systems, engineered wood products, and fire-tested interior assemblies. As a result, there are a lot of lessons learned and solid experience there.

When it comes to fire design, I can vouch that surface burning characteristics are one of the most misunderstood parts of fire design.

Not because the science is complicated, but because the test results are often taken at face value, without understanding what they actually represent in a real building.

I’ve reviewed specifications where ASTM E84 ratings were technically correct yet unusable. I’ve watched projects stall during plan review because a “Class A” assumption didn’t hold up under scrutiny. And I’ve had more than a few conversations with Authorities Having Jurisdiction (AHJs) that started with, “We thought this was compliant…”

Today, I’ve decided to write down my knowledge on the topic to avoid confusion, explaining surface burning characteristics the way architects actually need to understand them.

So if you are an architect, let’s walk through this together.

TL;DR – Quick Takeaways

- Surface burning characteristics describe early flame spread and smoke generation, not fire resistance or structural performance.

- ASTM E84 (the Steiner Tunnel Test) is the standard test method that the IBC primarily relies on for regulating interior finishes under Section 803.

- A Class A rating means limited flame spread under test conditions -it does not mean a material won't burn, and it doesn't supersede other code requirements.

- All interior finish classes (A, B, and C) share the same smoke developed index limit of 450

- Exposed mass timber is still subject to IBC 801/ASTM E84 requirements depending on the location.

- Most code compliance issues stem from mismatched test data, incomplete submittals, or specification gaps.

If ASTM E84 has ever felt vague or inconsistently enforced, the sections below will explain why.

What Are Surface Burning Characteristics?

Surface burning characteristics describe how an exposed interior surface reacts when flame first reaches it. The focus is narrow but very important, and it evaluates how quickly fire spreads along the surface and how much smoke is generated during this early phase.

Confusion arises when it comes to what surface burning characteristics are not intended to measure.

They do not tell you how long a wall or ceiling will remain intact in a fire. They don’t address load-bearing capacity, burn-through time, or structural collapse. Those concerns are covered by fire-resistance testing (IBC Chapter 7), not by ASTM E84.

In the IBC, surface burning characteristics come into play under Section 803, which governs interior wall and ceiling finishes. Once a material is exposed, its surface behavior matters.

The code regulates this based on occupancy type, building construction, sprinkler protection, and location of the materials within the building.

Understanding ASTM E84 (The Steiner Tunnel Test)

ASTM E84 (also published as UL 723 and referenced in NFPA 255) is commonly called the Steiner Tunnel Test. It's been the industry standard for evaluating surface burning performance of interior finishes since the 1950s. Although the test has faced criticism due to its inherent limitations, it remains the test method the IBC relies on.

How the test works in practice is rather straightforward. A material sample, nominally 20 inches wide and 24 feet long, is mounted to the ceiling of a horizontal tunnel. Gas burners at one end then produce a controlled flame exposure. Observers then track how far and how fast the flame travels across the sample surface.

The purpose of this test is to create two key values:

- Flame Spread Index (FSI) – a measure of how quickly fire progresses along the surface

- Smoke Developed Index (SDI) – a measure of optical density from combustion

Over the years, a common misconception I encounter about this test is thinking that these values are absolute measurements. But instead, they’re comparative indices, normalized against two reference materials tested under identical conditions.

Those two reference materials are select-grade red oak, which is assigned an FSI of 100, and fiber-cement board, which is assigned an FSI of 0.

The material being tested receives an index score calculated based on where it falls relative to the reference material’s benchmark score.

For example, a material with an FSI of 25 doesn't spread flames at "25% the rate" of anything specific. It's simply performing at the boundary between Class A and Class B under this particular test protocol (we’ll cover the classes in the next section).

Here are other key details to be aware of when using these scores and materials in practice:

Test orientation is on the ceiling: Materials perform differently on walls versus ceilings, but E84 is typically conducted ceiling-mounted; the key is that your test mounting matches the intended use/mounting standard.

Specimen thickness and substrate affect results: Mounting and substrate are prescribed by the test/mounting standard and can materially change results. Verify the tested mounting matches the intended installation.

The standard test runs for 10 minutes: Some laboratories perform extended-duration tunnel tests for supplemental information, but these are not part of the ASTM E84 classification and are not referenced by the IBC.

ASTM E84 Fire Classifications (And What They Actually Mean)

Most architects are familiar with the labels Class A, B, and C, but the application of these classifications is where things become nuanced.

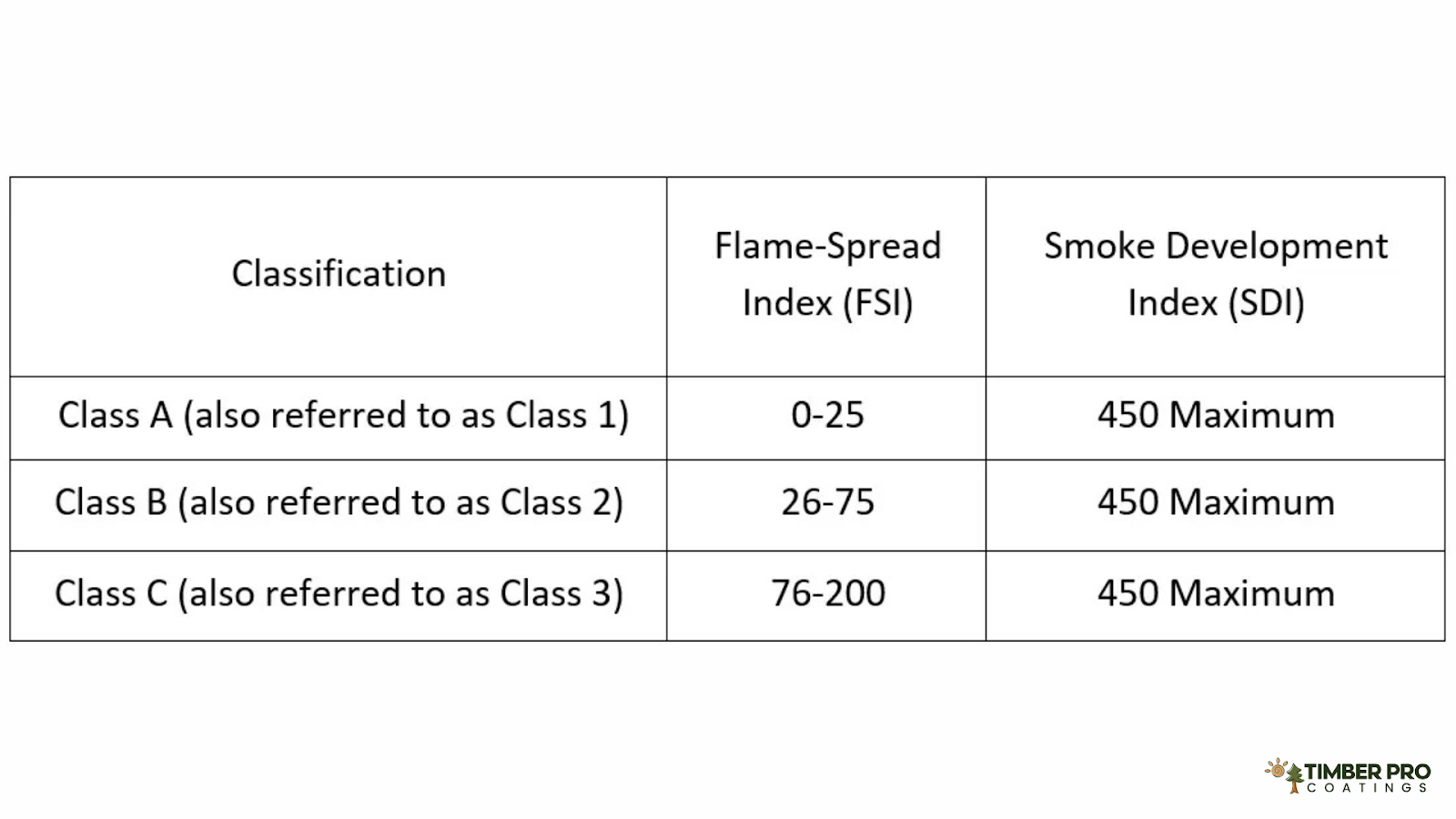

To start, here’s the breakdown of each class:

Class A (FSI 0–25, SDI 0–450)

Class B (FSI 26–75, SDI 0–450)

Class C (FSI 76–200, SDI 0–450)

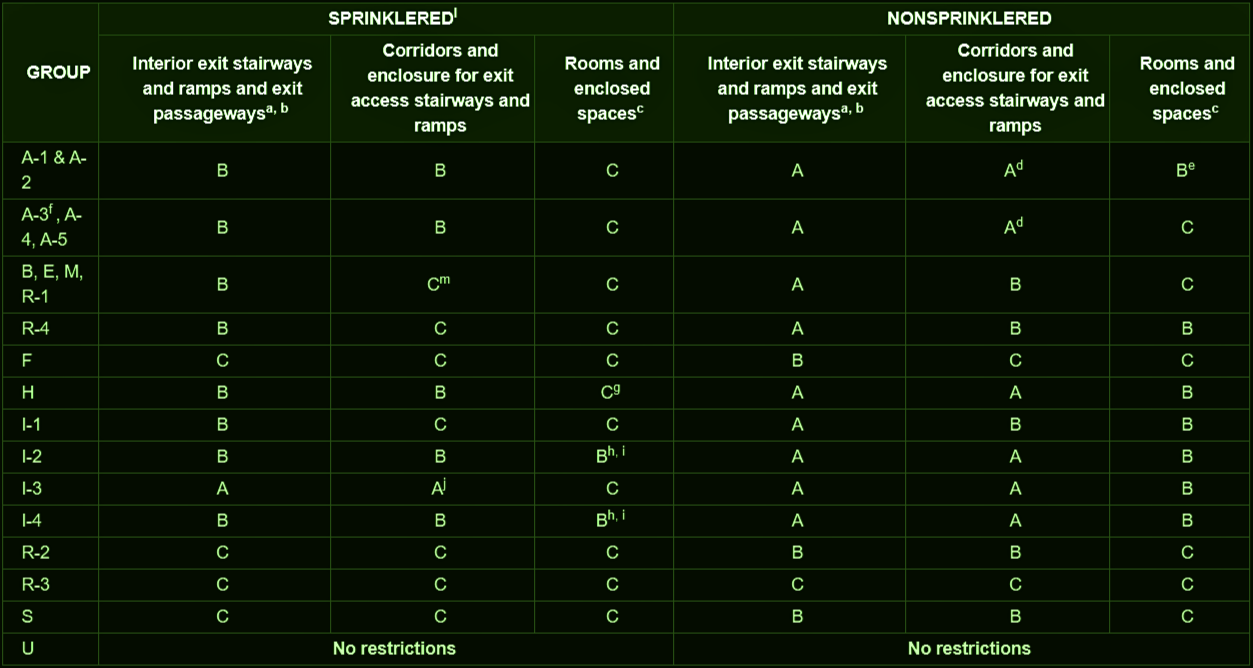

Table 803.13 sets the required class by occupancy and location (and can change with sprinklers).

Unit statement

The table is given in inch–pound units, where 1 inch equals 25.4 millimeters and 1 square foot equals 0.0929 square meters.

a. Class C interior finish is permitted for wainscoting or paneling up to 1,000 square feet in a grade‑level lobby, when it is applied directly to a noncombustible base or to furring over a noncombustible base and includes fireblocking as required by Section 803.15.1.

b. Except for Group I‑3, in buildings less than three stories above grade, Class B finish is allowed on interior exit stairs and ramps in nonsprinklered buildings, and Class C finish is allowed on interior exit stairs and ramps in sprinklered buildings.

c. Classifications for rooms and enclosed spaces are based on the spaces defined by partitions. Where structural elements require a fire‑resistance rating, enclosing partitions must run from floor to ceiling. Partitions that do not fully enclose both sides are treated as enclosing spaces on both sides, and those spaces are considered a single room or space. The actual use of the room or space governs the required finish, not the overall building occupancy.

d. Lobbies serving Group A‑1, A‑2, and A‑3 occupancies must have finishes that are at least Class B.

e. Class C interior finish is permitted in places of assembly with an occupant load of 300 persons or fewer.

f. In places of religious worship, decorative wood such as trusses, paneling, and chancel furnishings is permitted.

g. In buildings with more than two stories, interior finishes must be at least Class B.

h. Class C interior finish is permitted in administrative areas serving the listed occupancies.

i. Class C interior finish is allowed in rooms designed for no more than four occupants.

j. Class B materials may be used as wainscoting up to 48 inches above the finished floor in corridors and exit access stairs and ramps.

k. Finish materials permitted elsewhere in the code are also acceptable under this section.

l. Provisions that reference sprinklered conditions apply only where an automatic sprinkler system is installed in accordance with Sections 903.3.1.1 or 903.3.1.2.

m. Corridors in ambulatory care facilities must use Class A or Class B interior finishes.

An important detail in these classifications is that all three classes share the same smoke developed index limit of 450. If an interior wall or ceiling finish material exceeds that threshold, it’s disqualified, regardless of flame spread performance. (Note: Other materials, such as plastics or foams, can have threshold values lower than 450 under IBC 803)

One of the common errors when applying these classes to building plans is assuming that specifying Class A materials solves all code-related issues.

When specifying Class A materials, you still need to consider the following:

- The specific occupancy permits allow that finish in that location (Table 803.13)

- That smoke development is below 450

- That the tested configuration matches the installation

As a quick reference, the classification (A, B, or C) tells you how the material performed in the tunnel test. The code tells you specifically where you're allowed to use them.

Surface Burning vs. Fire Resistance - How They Differ

One of the most common misconceptions I encounter is that ASTM E84 is a fire-resistance test.

It isn’t.

Surface burning characteristics deal with how fire spreads across a surface. Fire-resistance ratings deal with how long an assembly can experience fire and maintain structural integrity.

The IBC treats these separately for a reason. Fire resistance is governed by Chapter 7 and evaluated using tests like ASTM E119 (or UL 263). Those tests expose an entire assembly, like studs, sheathing, insulation, and finishes, to a time-temperature curve that simulates a fully developed fire.

The assembly is then rated based on how long it prevents flame passage, heat transmission, and structural collapse.

By contrast, ASTM E84 evaluates only the surface layer under a 10-minute exposure. It provides no information about what happens after the surface ignites, how the assembly behind it will perform, or whether the wall will still be standing in thirty minutes.

With that in mind, let’s look at what that means in practice:

Example 1: A Type III-A building might require 1-hour fire-resistance-rated interior bearing walls, based on IBC Table 601. That rating comes from a tested assembly, which can consist of steel studs, gypsum board, insulation, and specific attachment methods. The wall finish, if exposed, must also meet surface burning requirements under Section 803. Both requirements apply, and one does not satisfy the other.

Example 2: A corridor wall in a Group I-2 hospital may require both a fire-resistance rating under IBC Section 407 and a specific interior finish classification under Table 803.13, depending on sprinkler protection, corridor function, and the adopted IBC edition.

In summary, fire resistance keeps the fire from spreading through the assembly. Surface burning characteristics limit how fast it spreads across the assembly. The code enforces both separately, so you need to consider both.

How Mass Timber Fits into ASTM E84

Mass timber has changed how we think about wood in a fire, but it hasn’t eliminated surface burning requirements. In reality, it’s made the conversation more technically nuanced.

When mass timber is left exposed as an interior finish, it's generally regulated under IBC Section 803, unless a specific code provision or exception permits otherwise.

Another complication is that untreated mass timber often does not meet Class A or Class B requirements. Depending on species, layup, surface condition, and panel thickness, tested FSI values commonly fall within the Class B or Class C range, with significant variation between products.

Most projects I've worked on use one of three strategies to mitigate this issue:

- Fire-retardant coatings: Using intumescent or non-intumescent topical treatments tested per ASTM E84

- Fire-retardant-treated wood: Using pressure-treated lumber or veneers that meet IBC Section 2303.2

- Noncombustible cladding or linings: Using gypsum board, cement board, or other materials that encapsulate the wood where required.

Fire-Retardant Treatments and Coatings

Fire-retardant-treated wood and intumescent coatings are commonly used to achieve acceptable surface burning characteristics for exposed wood. Both work, but they're fundamentally different systems. In practice, this means the specification details matter far more than the product label.

From experience, the most important things to verify are:

- The ASTM E84 test includes the exact finish or coating.

- That the tested thickness matches what’s being installed. A treatment that achieves Class A in 2x6 Douglas fir may not perform identically in 2x10 southern pine.

- Confirm the treatment is listed for interior applications per IBC Section 2303.2.1. Not all FRTW is rated for interior use.

Where Specifications Commonly Go Wrong

Most ASTM E84-related delays don’t come from poor performance. They come from documentation gaps.

Common issues to look out for are test data that doesn’t include the applied finish, and results based on thinner samples than what’s installed. Another common shortfall is vague language like “ASTM E84 compliant” without reported flame spread or smoke values.

For example, the specification says: "All exposed wood finishes shall comply with ASTM E84 Class A."

The problem is that there is no flame spread index, no smoke developed index, no test report reference, and no product identification. This vague language leads to inconsistent interpretation from all involved, which leads to delays.

The next most common issue is test data submissions that don't match the installation. Issues such as different substrates, material thickness, and surface preparation can all lead to issues.

Listing all of the common specification issues I’ve seen over the years could be a complete article on its own. But below are the most common areas where things go wrong.

Vague product identification: The problem with language such as "approved equal" is that fire performance isn't fungible.

No applicator qualifications or inspection requirements: Fire-retardant coatings are only as good as their application.

No plan for field verification: Materials or techniques can change at the last minute during the installation, which can leave an issue until the inspection happens.

Final Thoughts

ASTM E84 isn’t meant to limit design. It’s meant to make early fire behavior more predictable.

When architects understand what surface burning characteristics actually measure, and specify them accurately, exposed wood, mass timber, and innovative interior finishes become easier to defend, not harder.

After more than two decades working with these systems, my advice is simple:

Treat ASTM E84 as part of the design conversation from the start, not a box to check at the end.

FAQs

1. Does ASTM E84 apply to all interior materials?

No. It primarily applies to exposed interior wall and ceiling finishes regulated under IBC Section 803.

2. Can exposed mass timber meet Class A requirements without coatings?

Sometimes. It depends on species, thickness, and orientation, but many projects still require tested coatings.

3. Do clear finishes affect ASTM E84 results?

Yes. Even clear stains and sealers can significantly change flame spread and smoke development.

4. Does a Class A rating eliminate the need for rated assemblies?

No. Surface burning classification does not replace fire-resistance requirements under IBC Chapter 7

Get coating support for your next mass timber project

Fill out the form below to schedule a personalized consultation with our commercial team. We'll help you identify the right TimberPro solutions for your specific application.

Speak with a consultant

M-F 9AM - 5PM PST, Saturday & Sunday Closed

.svg)

%201.svg)

%201.svg)

%20(1).jpg)

%20(1).jpg)

.svg)

%20(1).avif)

%201.svg)

%201.svg)